Artist’s Statement

By

Prof. Alex J. Feingold

Background History

I am a mathematician, a Professor in the Department

of Mathematical Sciences at Binghamton University, where I started as

an Assistant Professor in 1979. My field is a branch of algebra with

strong connections to mathematical physics, but I have often been able

to use geometric ideas and intuition in my research. Many aspects of

mathematics are related to art, and many artists have used concepts

from mathematics in their work. But it is much more rare to find a

mathematician actually doing art. Of course, most good mathematicians

would say that they are doing art whenever they prove a beautiful

theorem, but it is a kind of abstract art, which would be difficult for

a non-mathematical audience to appreciate or understand!

Aside from the ``art” accomplished in my

professional work, I have had an interest in making art through

sculpture at least since 1978, when I met Prof. Helaman Ferguson at my

first math conference. He was the first professor to invite me, as a

new Ph.D., to give a talk at another university. At that time he was a

professor at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, and he was kind

enough to invite me to give a colloquium talk there. While staying at

his house for a week, he showed me his garage workshop, where he worked

on stone sculpture as a hobby. He gave me some soapstone and some

simple hand tools, and showed me how to shape and polish it into my

first stone sculpture, imitating one of his. I took some other stone

samples home with me, and made a few more, including one small marble

piece, which was much hard material to shape! Before that influential

meeting, I found an exhibition of kinetic sound sculptures by Harry

Bertoia at the Johnson Art Museum at Cornell University. I thought they

were so interesting that when I returned to Drexel University (my first

job in Philadelphia, 1977-79), I tried making some myself (with help

from Stanley Cohen in their metal shop). My first attempt at making a

kinetic sound sculpture was in brass, and the base plate warped badly

from the heat of welding, but the result was still interesting. Others

I made of iron with quite thin rods making a light sound. After moving

to Binghamton in 1979, I made a few more sculptures of various kinds,

stone, wood and metal. I donated a couple kinetic sound sculptures to

the WSKG (local public TV/radio station) Art Auction, but was never

able to sell any until I put pictures on my university webpage.

My friend Helaman gave up his position as

Professor at Brigham Young University to pursue his sculpture fulltime

as a profession. He moved to Laurel, Maryland, and began a new career.

He has been very successful, and is one of very few people making

mathematics into stone and bronze sculptures. He has been very

important to me as a mentor, a friend and an inspiration, and his work

is now on a very high and ambitious level, mostly working on large

granite pieces by commission. A couple years ago I went to him with a

question about how I might use bronze casting to reproduce copies of a

mahogany wooden sculpture I had made. He suggested that I try to

contact someone in the Art Department of my university, so that I might

learn how to do such a thing myself, and not just take it to a foundry

for others to copy. That led me to contact Prof. Jim Stark, whose open

and welcoming attitude, and endless patience and good advice have

allowed me to seriously pursue my interest in sculpture for the last

two years. In fact, using the facilities of the Binghamton University

sculpture studio, I have been able to make many bronze sculptures

through the lost wax method, and a few by direct metal welding. I now

have enough completed pieces to have an exhibition, but I have not had

an opportunity until now to do so.

I am very excited about recent opportunities to exhibit my sculptures.

Below I will give some details and descriptions of several of the

pieces I have been able to exhibit, including the ideas behind the

pieces. I include some figures and pictures of the pieces.

Descriptions and Organizing

Concepts

Kinetic

Sound Sculptures

I have already said that one of my early

inspirations was seeing and hearing the kinetic sound sculptures (KSS)

of Harry Bertoia. In case you are not familiar with these, let me

describe them briefly, and then explain what I have done with the

concept. Flexible metal rods are attached to a metal base plate in a

pattern so that when they are pushed (by hand or by wind) the tops sway

and hit each other, causing sound vibrations in the rods and base. The

tops of the rods may carry thicker rods, giving the appearance of

cattails, and changing the period of motion as well as the tone of the

sound. The base plate usually rests on adjustable ``feet”, screws which

can be used to level or attach the sculpture on the floor or table, and

which transmit the vibration. I always make my kinetic sound sculptures

with a special symmetrical rod pattern that comes from my mathematical

research area. For example, there is an eight dimensional Lie algebra

(said to be of type A2) whose adjoint representation has weight diagram

consisting of a regular hexagon including the point at the center. I

have made several versions of that 7-rod KSS with different size top

rods to give different sounds, all but one sculpture made from the same

kind of silicon-bronze alloy used for casting in the sculpture studio,

and one made from stainless steel. I usually make them by threading the

rods, tops and bases so that the pieces can be screwed together,

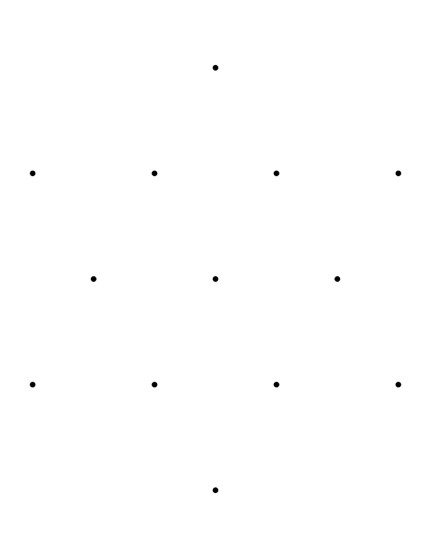

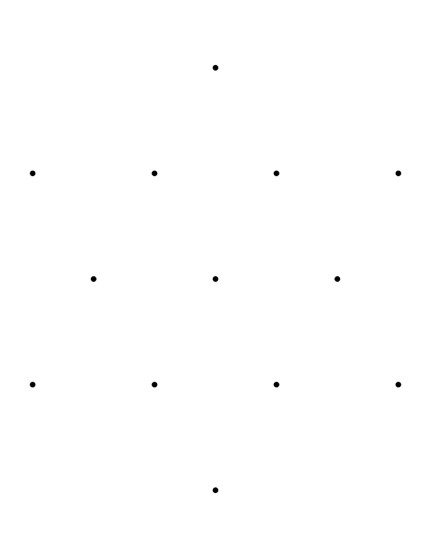

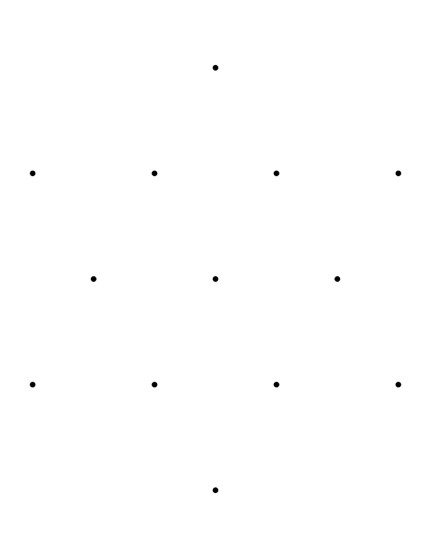

allowing disassembly for easy shipment. I have also made some 13-rod

KSS where the rod pattern comes from the adjoint representation of the

type G2 Lie algebra, which consists of a central point surrounded by

two hexagons of different sizes that fit together into a ``Star of

David” shown in Figure 1 below. The mathematical symmetries of these

patterns are captured by the Weyl group, which is a dihedral group

depending on the shape. There are infinitely many different possible

weight diagrams for each type of Lie algebra, but the patterns all have

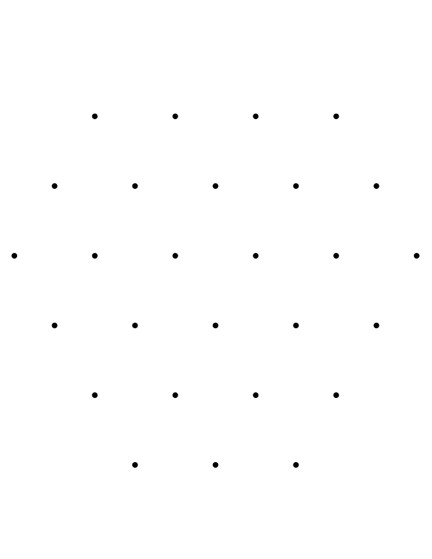

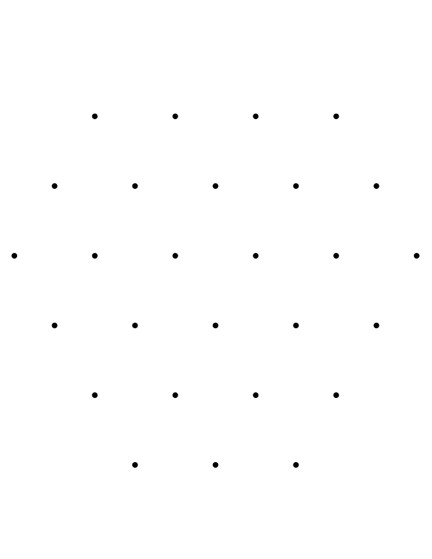

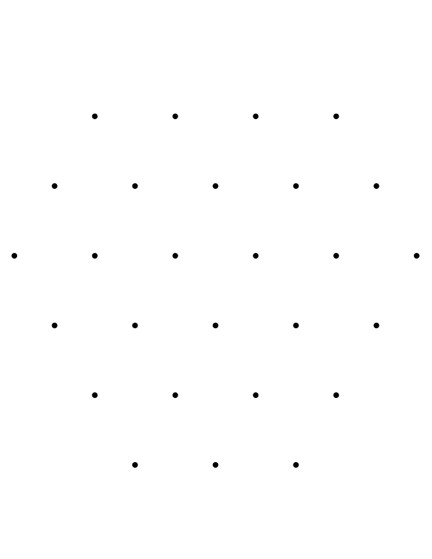

the same basic Weyl group symmetries. The largest one I ever made was a

commission for a client in Chicago, designed for an outdoor garden and

consisting of 27 rods based on a high dimensional representation of the

type A2 Lie algebra. The pattern of rods is shown below in Figure 2.

Here I am exhibiting a 7-rod KSS whose bronze base plate is mounted on

a larger wooden base of polished black walnut which adds considerably

to the appearance, sound and balance. Pictures of this piece are shown

in Figure 3.

Figure 1: G2 Weight Diagram – 13 Rod

Pattern

Figure 2: Type A2 Weight Diagram – 27 Rod Pattern

Figure 3: 7 Rod Hexagon KSS - Two Views

Knot

Sculptures

Several of my sculptures are related to the

topological theory of knots. A knot is a closed loop in space, which is

considered nontrivial if it curves around in such a way that it cannot

be continuously deformed into a simple circle. The simplest example of

such a nontrivial knot is the trefoil knot. When making such a knot

sculpture, one thinks first of choosing a shape for the cross-section,

that is, the shape of a slice at any point of the curve, perpendicular

to the path of the curve. I have made several sculptures based on the

trefoil knot, the simplest just from a bent rod (left over from a KSS!)

so the cross-section is just a circle. Another was cast with a

cross-section consisting of three circles, but it is not just three

parallel rods going around the knot separately. As they go around the

knot, they twist relative to each other, so that after going around the

knot once, the first rod leads into the second, the second into the

third, and the third into the first, making a single rod that goes

around the knot three times before closing the loop. This idea is

related to the mathematical concept of a fiber bundle, used in

differential geometry, where there is a big difference between the

local and the global structure of a manifold.

Two of the trefoil knots I have made were directly inspired by one made

by the sculptor John Robinson. He made the cross-section a rectangle,

and twisted it so that the rectangle formed a Mobius strip, the famous

one-sided figure made from a long strip of paper by curving it into a

cylinder, but giving a half-twist before connecting the ends. I made

one such Mobius trefoil in bronze by casting from a wax model, and

another by using the oxy-acetelyne torch to heat and bend a steel bar

into the twisted knot, finally welding the ends together. In each case,

I wanted the piece displayed in such a way that it could rotate in

space, and its reflection be seen from below, so I made a base plate as

I have used in my KSS, with a single rod in the center, its top

sharpened to a point, on which the knot is balanced. The plate is

polished so the viewer sees the reflection of the knot, but in the

steel version, the reflection was achieved by a sheet of plexiglass on

top of the plate. When struck by a hammer (a short metal rod provided

for that purpose), these knots produce a beautiful tone rich in

harmonics as the vibrations travel around and around the knot in both

directions! These sculptures should therefore be considered sound

sculptures. Pictures of these are shown in Figures 4 and 5. It is also

possible to hang these knots by wires from the ceiling, so that they

float just above the reflective bases. The short rod is used as a

hammer to make the knot ring.

Figure 4: Steel Trefoil Mobius Knot

Figure 5: Bronze Trefoil Mobius Knot

The third trefoil knot sculpture I have

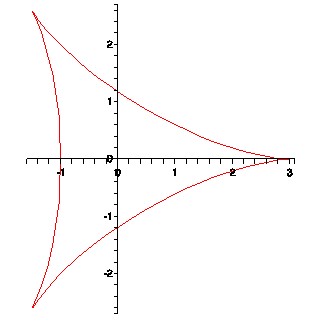

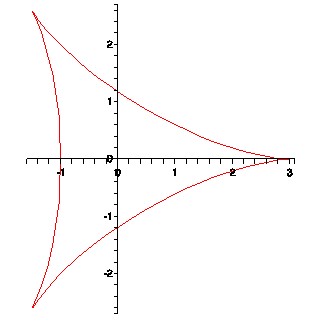

exhibited has the cross-section of a curve called a hypocycloid. It is

the curve made by a chosen point on a moving circle of radius R as it

rolls (without slipping) inside a larger circle of radius 3R. This

curve looks like a triangle whose sides are slightly curved inward, and

is shown in Figure 6. I made a bronze cast knot about 9” across with

this hypocycloid cross-section, twisting as it goes around the knot in

such a way that the edges made by the three vertices form one

continuous edge that closes up only after three circuits of the knot.

In the same way, the three surfaces made by the curving edges of the

hypocycloid also form one continuous surface that takes three circuits

of the knot to repeat, similar to the Mobius strip. I display this

piece hanging over a base of polished black walnut, supported by a

bronze rod bent into a parabola, held by a thin steel wire, but easily

removed for handling. A short length of bronze rod is set in a hole in

the base and can be removed and used as a hammer to strike the knot,

producing a beautiful tone. The sculpture, which has been sold, is

shown in Figure 7.

Figure 6: Hypocycloid curve

Figure 7: Bronze Trefoil Hypocycloid Knot

There are additional comments and pictures of

my work on my university internet webpages, which can be found using

any browser at the address:

http://www.math.binghamton.edu/alex/

under the heading ``Mathematical Sculptures by Alex Feingold”.

I would like to conclude with a statement of the goals and general

philosophy behind my work.

General Goals and Philosophy

Mathematics is the main inspiration for my

sculpture. I am certainly still trying to learn technique and

craftsmanship, exploring my limits and capabilities. There seem to be a

very large number of ideas from mathematics that lend themselves to

expression in sculpture, not just simple geometry, but using concepts

from quite advanced branches of math. I am very willing to study and

learn from others, but I hope I will eventually develop a unique voice

and vision of my own. I like best those small sculptures that can be

picked up and handled, so that the tactile impressions of the hands are

just as important as the image seen by the eyes. Surfaces, edges,

curvature and texture are the local characteristics felt, but the

larger global design is what appeals to the intellect and connects to

the wider world as well as to mathematical concepts. Motion and sound

are wonderful when incorporated into a sculpture, and I would like to

explore more ways of achieving that goal. I think my work will always

be on the abstract side, being mostly inspired by such concepts and

ideas rather than being representational. I greatly appreciate the

opportunity to exhibit some my work, and hope to get some reactions to

it from those in the art community.

Alex J. Feingold

Department of Mathematical Sciences

Binghamton University

This file last modified on December 2, 2007

Comments to alex@math.binghamton.edu